In April 2020 Magnus Robb and The Sound Approach published revised identification criteria for Spotted Flycatcher, Pied Flycatcher and Robin. I find these species, which all produce short, high frequency, sometimes buzzy calls, rather difficult to identify, perhaps partly due to presumptions(*) about what should and should not be flying around in Cambridgeshire in May. I have previously recorded a few of these calls but in May 2020 I recorded 20 individuals, some with multiple calls, providing an opportunity to try out these new criteria on a range of calls. Of course, none of these birds can be identified in any other way, so there is no way of independently verifying the identities.

* Note that in May I assume there should be a reasonable passage of Spotted Flycatchers at this latitude and that Robin migration should have long finished. So my assumption when processing all these calls is that they should be Spotted Flycatchers…

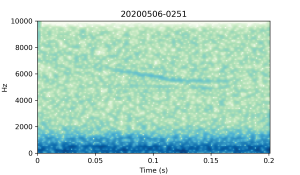

6 May

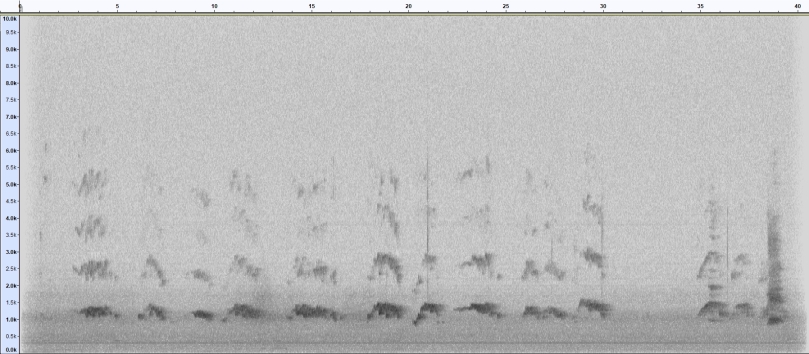

Bird 1: Rather faint. Two bands just visible. Call length = 105 ms, lower band 4.8–5.1 kHz, upper band 5.5–6.6 kHz. No spikes but call length and low frequencies suggest Spotted Flycatcher, although pro-Robin features are that bands approach much closer than 1 kHz. Identity uncertain.

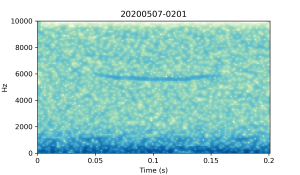

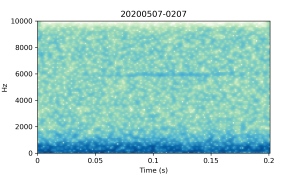

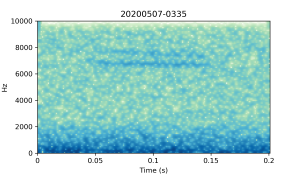

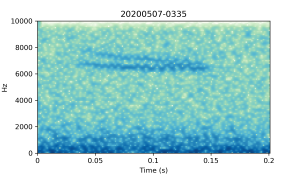

7 May

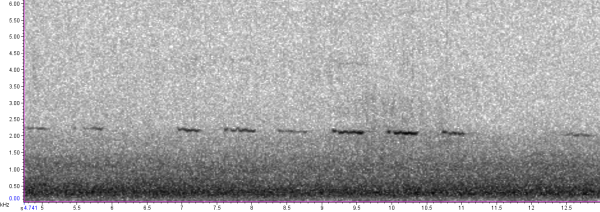

Bird 2: Distant; only one band visible. Longish call (104 ms) suggests Spotted Flycatcher. Frequency of band 5.7–5.9 kHz would be low for even the lower band of a Robin, so suggests this is a Spotted Flycatcher.

Bird 3: Another distant call with only one band visible (length = 106 ms, 5.9 kHz) and presumably also a Spotted Flycatcher. Given how variable these calls appear to be, yet how similar this is to the previous bird (which was only 6 minutes earlier), it is possible this is the same individual circling around.

Bird 4: Two calls 13 s apart, presumably from one individual. Higher frequency (6.3–7.7 kHz) than other birds but call still quite long (99 ms and 110 ms). No obvious spikes but fine shallow modulations throughout both calls. Bands close and tapering, plus frequency range suggest Robin but fine modulations seem not to fit. Identity uncertain.

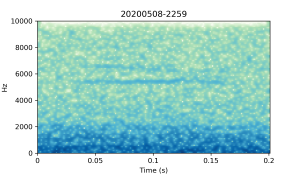

8 May

Bird 5: A long call (127 ms) with suggestion of shallow spikes on lower band. This and lowish frequency 5.3–6.6 kHz suggest probably a Spotted Flycatcher.

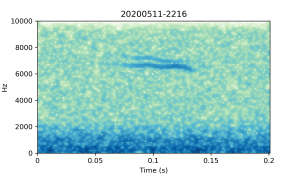

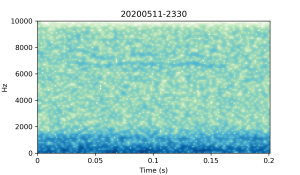

11 May

Bird 6: a short call (89 ms), no spikes, slight kinks, tapering, and higher frequency 6.6–7.4 kHz suggest possible Robin.

Bird 7: long call (134 ms) suggestive of Spotted Flycatcher but lack of spikes and higher frequency (6.6–7.7 kHz) point more towards Robin. Identity uncertain.

15 May

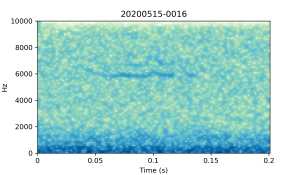

Bird 8: intermediate call length (96 ms) and frequency 5.9–7.1 kHz. Call a bit distant and broken, especially top band. Possibly a Spotted Flycatcher.

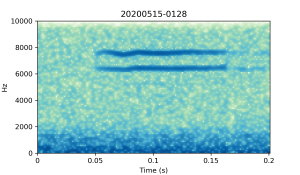

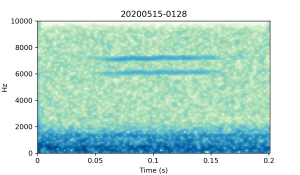

Bird 9: Two calls, 13 s apart. Long calls (112 ms) and general shape suggest Spotted Flycatcher but relatively high frequency (6.1–7.7 kHz). A Spotted Flycatcher at upper end of range?

19 May

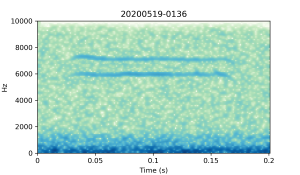

Bird 10: A very long call (141 ms) with possible small spikes on lower band. Above average frequency (5.6–7.3 kHz) but within the range for Spotted Flycatcher.

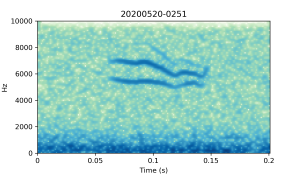

20 May

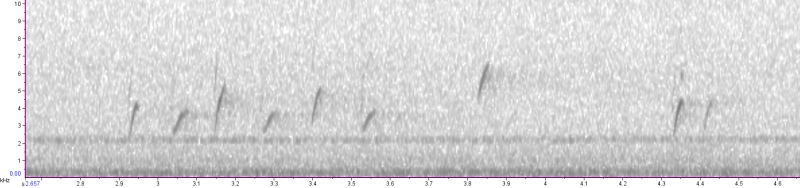

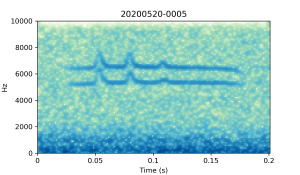

Bird 11: A very long call (158 ms) with 3 distinct spikes and low frequency range (5.2–6.5 kHz) indicative of Spotted Flycatcher.

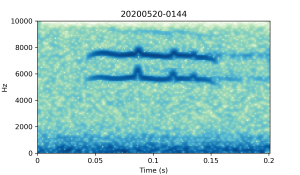

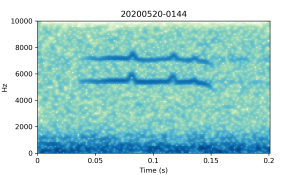

Bird 12: Three calls recorded, first very faint (not shown); calls spaced 17 s and 8 s. Longish calls (113 ms) with 3 spikes. First closes call has suggestion of third higher band. Structure and mid-range frequencies (5.2–7.6 kHz) matching Spotted Flycatcher.

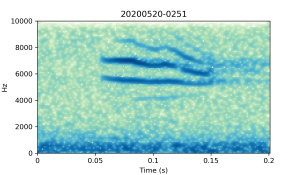

Bird 13: Two calls 11 s apart. Both calls have multiple bands, which are generally tapering with obvious kinks suggestive of Robin. However, frequencies for strongest bands are low for Robin: lower band 5.0–5.7 kHz and upper band starting 7.0 kHz but dropping to 6.0 kHz. Robin calls at 6 kHz seem rare judging by Sound Approach info. First call also quite long (107 ms; second call apparently only 83 ms). Note that the apparent tapering of the call could be exaggerated by the presence of additional bands; the two strongest bands show tapering similar to other calls above. Identity uncertain.

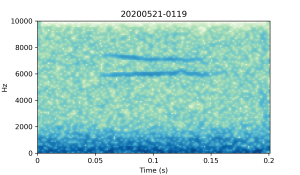

21 May

Bird 14: Fairly average calls – medium length (95 ms) and medium frequency 5.8–7.4 kHz suggest a spike-less Spotted Flycatcher.

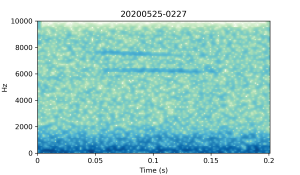

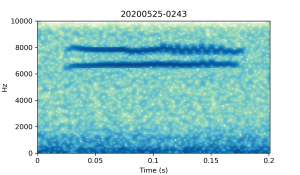

25 May

Bird 15: 91 ms length. Frequency range 6.2–7.7 kHz are at the upper end of the Spotted Flycatcher range. Another spike-less Spotted Flycatcher?

Bird 16: a long call (155 ms) and fairly high frequency (6.9–7.9 kHz) with fine modulations in the upper band. Features seem contradictory, identity uncertain.

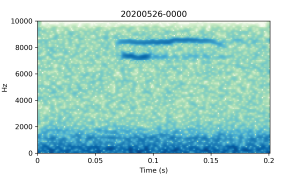

26 May

Bird 17: Medium length call(97 ms) but very high frequency (7.2–8.6 kHz). These features plus broken lower band suggestive of Robin.

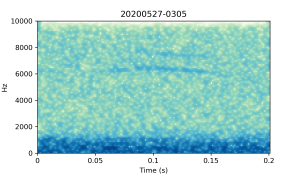

27 May

Bird 18: rather faint, short duration (85 ms) and frequency at upper end of Spotted Flycatcher range (6.2–7.8 kHz). Some hints of spikes, probably a Spotted Flycatcher.

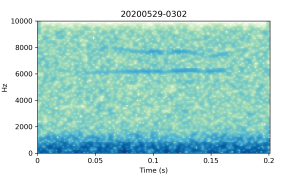

29 May

Bird 19: Longish call (129 ms), no spikes and moderately high frequency 6.1–7.9 kHz). Presumably a Spotted Flycatcher?

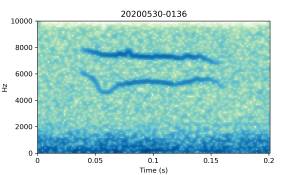

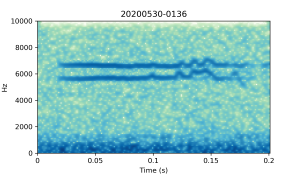

30 May

Bird 20: Two calls, 23s apart, presumed same bird, though very different in structure. First call lacks spikes but has a big downward kink suggestive of Robin. However, call length (124 ms) and frequencies (4.6–7.8 kHz) more suggestive of Spotted Flycatcher. Second call very long (170 ms) with small spikes and frequencies in Spotted Flycatcher range (5.6–6.7 kHz). Presumed Spotted Flycatcher.

Conclusions

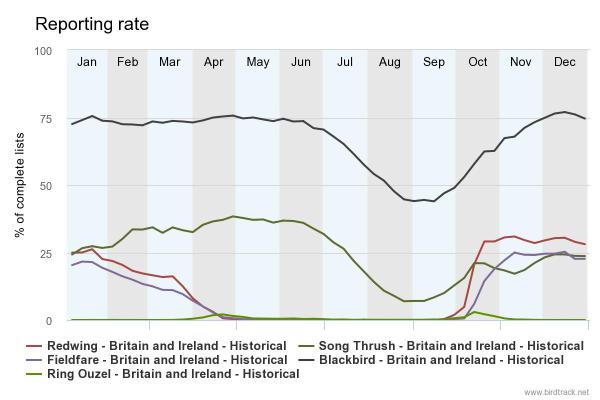

It appears that during May I recorded 2 probable Robins and 13 probable Spotted Flycatchers, with 5 more birds as yet unidentified. For a rapidly declining species it is nice to have recorded several Spotted Flycatchers. For the Robins, if indeed they are Robins, it begs the question, what are they doing migrating in May? As ever, nocmig raises just as many questions as it answers.

Identifying these 20 birds has been challenging, and while some birds fall neatly within the ranges described on the Sound Approach pages, some have conflicting features. In particular, many of the pro-Spotted Flycatcher calls had frequencies that were at the upper end of (or slightly above) the limits quoted by Magnus et al. As he points out, there is still much to learn for these and related species, and hopefully greater sample sizes of recordings from different places will help to clarify the picture. I imagine I may revisit the identities of these 20 birds as more information comes to light.

Metrics

The table below summarises the metrics extracted from the calls. Frequencies are measured excluding spikes. Note also for calls 2A and 3A I do not know whether the visible band was the lower or upper band. All measurements were made in Raven Lite. The spectrograms were produced in Python using bespoke code with a window length of 150 samples and overlap of 90%.

| Call | Number of bands | Length (ms) | Number of spikes | Lower bar Freq. min | Lower bar Freq. max | Upper bar Freq. min | Upper bar Freq. max |

| 1A | 2 | 105 | 0 | 4863 | 5107 | 5453 | 6572 |

| 2A | 1 | 104 | 0 | 5657 | 5880 | NA | NA |

| 3A | 1 | 106 | 0 | 5901 | 5921 | NA | NA |

| 4A | 2 | 99 | 0 | 6674 | 6877 | 7305 | 7691 |

| 4B | 2 | 110 | 0 | 6389 | 6633 | 6776 | 7712 |

| 5A | 2 | 127 | 2 | 5372 | 5433 | 6247 | 6572 |

| 6A | 2 | 89 | 0 | 6267 | 6735 | 6959 | 7366 |

| 7A | 2 | 134 | 0 | 6572 | 6755 | 7203 | 7712 |

| 8A | 2 | 96 | 0 | 5921 | 6267 | 6715 | 7142 |

| 9A | 2 | 112 | 0 | 6328 | 6491 | 7508 | 7671 |

| 9B | 2 | 112 | 0 | 6104 | 6165 | 7081 | 7203 |

| 10A | 2 | 141 | 1 | 5575 | 6064 | 6877 | 7325 |

| 11A | 2 | 158 | 3 | 5209 | 5290 | 6348 | 6532 |

| 12A | 2 | 113 | 3 | 5514 | 5738 | 7142 | 7590 |

| 12B | 2 | 113 | 3 | 5209 | 5514 | 6918 | 7223 |

| 13A | 5 | 107 | 0 | 5229 | 5758 | 5982 | 7040 |

| 13B | 3 | 83 | 0 | 5005 | 5616 | 5779 | 6979 |

| 14A | 2 | 95 | 0 | 5840 | 6267 | 7020 | 7366 |

| 15A | 2 | 91 | 0 | 6165 | 6328 | 7427 | 7691 |

| 16A | 2 | 155 | 0 | 6493 | 6700 | 7690 | 7944 |

| 17A | 2 | 97 | 0 | 7230 | 7437 | 8243 | 8565 |

| 18A | 2 | 85 | 0 | 6194 | 6447 | 7391 | 7828 |

| 19A | 2 | 129 | 0 | 6148 | 6355 | 7207 | 7898 |

| 20A | 2 | 124 | 0 | 4628 | 5618 | 6884 | 7828 |

| 20B | 2 | 170 | 2 | 5618 | 5664 | 6539 | 6700 |